Overreaching Much? Canadian Commercial Surrogacy Law Violates the Charter

Overreaching Much? Canadian Commercial Surrogacy Law Violates the Charter

Assisted Human Reproduction Act (AHRA) makes commercial surrogacy illegal in Canada. Under s.60 of the act, any person who contravenes this prohibition on commercial surrogate services is liable “to a fine not exceeding 0,000 or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding ten years, or to both; or is liable […] to a fine not exceeding 0,000 or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding four years, or to both.” Really? In Canada? The Act’s punitive approach towards commercial surrogacy not only raises the repugnant specter of governmental interference in matters implicating our most fundamental notions of privacy as Canadians, but it may well be unconstitutional under s.7 and s.15 of the Charter. Yet, since the adoption of the AHRA, there has been curiously little debate or outcry from either the Bar or the public. Considering the gravity of the interests at stake, the absence of thoughtful criticism is striking and disheartening. In an attempt to jump-start a long overdue debate on the merits of well-intentioned, but seriously misguided and harmful provisions dealing with commercial surrogacy, this article offers a an informal and rudimentary Charter analysis of commercial surrogacy provisions. I submit the following as the conclusions of this Charter analysis:

a) Commercial surrogacy prohibition in AHRA violate s.7 liberty and security interests of women who choose to act as surrogates, in a manner that is not in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice, and that cannot be justified in a free and democratic society.

b) Commercial surrogacy prohibition in AHRA also violates equal protection guarantee under s.15 of the Charter, as discriminating against:

Heterosexual persons with fertility problems, by denying or severely limiting meaningful access to paid surrogacy, which is their sole means of biological procreation

Homosexual persons, as the criminal prohibition against commercial surrogacy disproportionately effect gays and lesbians by frustrating access to the only practical method of procreation available to them – commercial surrogacy.

Section 7 Analysis:

Security Interest

The prohibition on commercial surrogacy runs contrary to a long line of jurisprudence tracing back to Morgentaler. Rather than preventing harm to surrogate mothers, the prohibition of paid surrogacy creates optimal conditions for their exploitation. Despite the penalties, there is little doubt that commercial surrogacy will persist, as people desperate to have children will find new ways to circumvent the laws standing in their way. The severity of the Parliament’s response will only drive these arrangements underground – thereby disempowering the surrogates. Importation of severe sanctions and criminal stigma into the reproductive sphere increases the likelihood that surrogates will endure more exploitative dynamics than they otherwise would, in fear that reporting would lead to criminal sanctions against them. As it currently stands, the Act’s heavy-handed approach de facto deprives paid gestational carriers of legal counsel. Diminished willingness to seek out legal advice means that paid surrogates cannot obtain optimum benefit of the surrogacy arrangements and leaves their interests unprotected.

In a medical context, bringing the commercial surrogacy arrangements into the open is not only prudent, but necessary to protect lives, health and emotional well-being of surrogate mothers. In light of foreseen, as well as unforeseen complications associated with pregnancy, protection of a surrogate mothers’ health is an interest that is of sufficient importance to invoke the protection of section 7 of the Charter. Criminalization of commercial surrogacy is likely to discourage proper pre-natal care and monitoring, thus placing the surrogate carrier and the child in a situation that has a potential to jeopardize both their health and in extreme cases, life.

The prohibition on commercial surrogacy and the accompanying criminal sanctions provided in section 60 of the AHRA amount to an impermissible state interference with surrogate carrier’s bodily integrity. The impugned provisions of the Assisted Human Reproduction Act therefore infringe the security interests of surrogates.

Liberty Interest

Morgentaler and the decisions that followed have firmly established that a woman’s sphere of reproductive autonomy is sacrosanct in Canadian law. Charter is a highly libertarian document whose protection of people’s freedom to act in their own interests without undue state interference is buttressed by voluminous case law arising out of s.7 jurisprudence.

All parties to a commercial surrogacy contract understand that a pregnant woman has absolute right to abort or not abort any fetus that she is carrying. Nevertheless, the Act’s draconian penalties enshrine into law an ancient and discredited presumption that women lack the intellectual wherewithal, wisdom and ability to make an informed decision whether to enter into a commercial surrogacy arrangement. The paternalism with which the current law treats women as children, no matter what their age, strikes at the heart of the self-determination interest. Implicit in AHRA is a repugnant assumption that profit automatically vitiates consent and impairs a surrogate’s ability to make informed decisions.

If a woman’s sphere of privacy and self-determination includes her right to chose whether or not to have an abortion, it must certainly encircle the other side of the same coin – her ability to knowingly and intelligently agree to gestate and deliver a baby for intending parents. To claim otherwise risks perpetuating the stereotypes of gender inferiority that have prevented women from attaining equal political and personal rights. To resurrect this view is to foreclose a personal and economic choice on the part of a surrogate in violation of her s.7 rights.

It is a well-established principle of constitutional interpretation that the law that is shown to be arbitrary or irrational will not be in accordance with principles of fundamental justice, and will thus infringe section 7 of the Charter.

At first blush, the prohibition of commercial surrogacy is rooted in genuine concerns. The fear that the payment for surrogate services may lead to the exploitation of poor and disadvantaged women is the driving force behind the prohibition of commercial surrogacy. This laudable social goal, however, is ill served by the current statutory regime under AHRA. To determine whether commercial surrogacy agreements have the propensity to exploit women, a narrowly tailored inquiery must be conducted. First step in the analysis is to ask whether compensation for services is the only or even a predominant factor that induces the surrogate mothers to undertake pregnancy, and whether a payment to a surrogate for her services can, standing alone, be construed as exploitative or demeaning.

The Parliament fragmented surrogacy into altruistic and commercial — regulating the first and prohibiting the latter. We cannot uncritically assume that altruistic arrangements are, by their very nature, any less or more abusive or exploitative than commercial surrogacy arrangements. We cannot defer to the proposed generalization as to the effects of either form of surrogacy since exploitation is inevitably the matter of degree and circumstance. Determination of the level at which compensation or social pressure become exploitative must take into account the specific circumstances of each case and weigh the factors in the light of existing common law.

Separation between altruistic and commercial surrogacy in the AHRA is arbitrary and vague. We are all well aware of to the danger of exploitation in commercial surrogacy arrangements. Nevertheless, it is conceivable that in commercial arrangements, the surrogate may be bearing a child out of a genuine intention of the heart, while the “altruistic arrangements” could result out of sheer emotional coercion by family members or other actors. The Act does little to address this conundrum.

In attempting to determine which of the two types of surrogacy is more exploitative, it should not be forgotten that in cases where there is a prior subsisting relationship between the surrogate and the intended parents, there are increased chances of emotional exploitation. Private, undue influence can be equally as harmful as commercial exploitation of one’s reproductive capability .As Uma Naraya writes in “The ‘Gift’ of a Child: Commercial Surrogacy, Gift Surrogacy, and Motherhood” in Patricia Boling, ed., Expecting Trouble: Surrogacy, Fetal Abuse, & New Reproductive Technologies (Oxford: Westview Press, 1995) 177:

“Vulnerability is not, unique to commercial surrogates. Since gift surrogacy may often take place under circumstances that encourage coercive intrusions, the risk of intrusions may be even greater. Gift surrogates who have prior friendship or kinship ties with the receiving parents may be as economically or psychologically vulnerable as commercial surrogates to intrusive procedures. The gift surrogate, though unpaid, may be economically dependent on the commissioning parents or members of their family. The fact she is unpaid is as likely to be a symptom of the family’s power in taking her reproductive services for granted as an indication that she is acting out of un-coerced altruism.”(at p. 179)

In light of this argument, commercial surrogacy arrangements present themselves not merely as a neutral alternative, but rather, as a more appropriate form of surrogacy that is devoid of family dynamics and conducive to regulation.

The prohibition of commercial surrogacy is premised on the concern that financial inducements in commercial surrogacy contracts tend to exploit or dehumanize women, especially women of lower economic status. The proposition that poor women are disproportionately exploited in commercial surrogacy context is not as universally accepted and indisputable as to allow its uncritical acceptance. This evil of exploitation of surrogates is unsupported by any cogent evidence of pervasive of generalized coercion or duress.

While statistics may show that women of lesser means serve as surrogates more often than wealthy women do, there are no indications that commercial surrogacy exploits poor women to any greater degree than economic necessity in general exploits them by inducing them to accept lower-paid or otherwise undesirable employment. In fact, although monetary reasons are one of the motivating factors among surrogates, other factors include a desire to provide an infertile or *** couple with a baby and the desire to experience pregnancy without the responsibility of having to raise a child. Attitudes acquired in the course of working in the fields of medicine or education also influence the decision-making of surrogates who generally come from lower-middle and middle classes.

The proscribed differentiation between different forms of surrogacy is itself exploitative and thus contrary to the principle of human dignity. The legislative aversion to the concept of payments made to the surrogate for her services creates a situation of economic and social inequity. To use a surrogate mother’s reproductive capabilities without adequate compensation for her efforts only affirms the deleterious notion that women are no better than natural incubators.

Prohibition on payments harkens back to the Dark Ages of judicial reasoning where the women’s work in the private (home) sphere was considered unworthy of compensation. Such position is at complete variance with our fundamental Constitutional concepts. To affirm the legislation as it currently stands would send a message that a devaluation of women’s labour is acceptable. It is not.

Finally, in balancing the competing interest, we must consider an aspect of commercial surrogacy that is routinely overlooked — the emotional and legal vulnerability of the commissioning parents. The position of the intended parents is not prima facie and immutably a position of power and control over the surrogate mother. Coupled with the autonomy over her body, surrogate mother’s control over the life and health of a child that she is carrying places her in a potent position to dictate her own terms for the service that she is providing. Therefore, any legislative scheme that is seeking to address exploitation dynamic in commercial surrogacy context must address the intended parents’ side of the argument as well.

Not only does the prohibition on commercial surrogacy in AHRA amount to a removal of a surrogate’s decision making power, but it also not minimally impairing. If the purpose of the prohibition is to protect surrogates, a blanket prohibition on all commercial surrogacies is a legislative overreach. Since not every, or even most commercial surrogacy arrangement are exploitative, the same goal can more appropriately be met through an individual approach to the offence, such as case by case prosecution of individuals who commit act of exploitation. Appropriate sanctions under the Criminal Code - subject to all the appropriate safeguards and a requisite standard of proof - are adequate to address what we must hope would be the rare situations of exploitation of surrogates. Otherwise, the government arbitrarily paints all players in surrogacy arrangements as apriori guilty of exploitation.

In the absence of a legitimate government interest, it is a denial of fundamental justice to deprive surrogates of the ability to carry a child for fair compensation. To claim otherwise would require the courts to endorse biased, arbitrary or irrational use of the criminal law power, contrary to s.7 of the Charter.

S.15 Analysis

At issue here is the claim that the Parliament has violated the rights of infertile persons on the basis of disability and homosexual persons on the basis of ****** orientation contrary to s. 15 of the Charter, because the prohibition on commercial surrogacy denies these two groups an opportunity to procreate through the use of Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ARTs).

As established in Law and affirmed in Hodge, each step in s. 15(1) analysis must proceed on the basis of a comparison. While the claimants may choose their comparator group, the court reserves the right to refine or change a comparator group. The comparison required is to a comparator group with whom the claimants share characteristics relevant to qualification for the benefit or burden in question.

The benefit sought in this context is access to commercial surrogacy arrangements for homosexual and/or heterosexual persons who are medically unable to undergo pregnancy or to conceive without the aid of ARTs. The essence of this issue is that the criminal prohibition on commercial surrogacy disproportionately effects homosexual and/or infertile persons and couples who cannot conceive without a recourse to ARTs. The only difference between homosexual persons and infertile heterosexual persons (or couples) and the comparator group lies in their (in)ability to procreate. Heterosexual persons (and couples) who are able to procreate without the aid of ATRs are proper comparators for the purposes of the current s. 15(1) analysis.

A) Differential Treatment Is Established - Adverse Discrimination

The first step in s. 15(1) analysis is for the claimants to show the required differential treatment. *** men or infertile heterosexuals cannot demonstrate that the benefit claimed, namely access to commercial surrogacy arrangements, was denied to them in a discriminatory manner. AHRA creates a blanket prohibition that applies equally to everyone, regardless of their reproductive capability or ****** orientation. Based on the wording of the relevant sections of AHRA, we would not be able to find any direct discriminatory intent on the part of the Legislature, as the relevant sections of AHRA do not draw a formal distinction between the claimants and their comparator group on the basis of one or more personal characteristics.

Nevertheless, the lack of formal differentiation is not dispositive of the finding of discrimination. It has been repeatedly held that identical treatment will not always constitute equal treatment. As the Supreme Court of Canada established in Vriend and Eldridge, a seemingly neutral law that fails to take into account the claimants’ already disadvantaged position in the society, resulting in a substantially different treatment between the claimant and others, will be found prima facie discriminatory.

The adverse effect discrimination is either an unintended effect of a legislation that disproportionately affect a disadvantaged group or a legislative omission to include or accommodate a group of disadvantaged individuals. In Vriend, the Court held that there was no need to show an invidious motive or mala fides on the part of the Parliament in order to establish discrimination. Criminalization of commercial surrogacy arrangements does not affect healthy heterosexual couples from procreating, as they are able to do so without the help of a surrogate, but it takes that possibility away from same-*** and infertile heterosexual couples.

Without expounding on many complexities that permeate adverse effect discrimination analysis, the impugned surrogacy provisions are facially neutral, but their operation affects adversely a disproportionate number of members of a group protected under the Charter and the provincial human rights laws — homosexual and persons who are biologically unable to conceive.

B) Differential Treatment Is Based on Enumerated or Analogous Grounds

There are two relevant ground of discrimination in this case:

1) “Physical disability”, which is an enumerated ground expressly included in s. 15(1).

2) “****** orientation” which this Court established in Egan as an analogous ground.

The first question is whether the inability to procreate without the aid of ARTs falls under the ambit of either or both of these grounds. It cannot be seriously disputed that a person unable to have a child has a physical disability. While this disability is not obvious to the eye, infertile individuals have a personal characteristic — inability to have a child — on the basis of which a distinction can be drawn. As long as the indicia of discrimination exist when the distinction is drawn, there is disability sufficient to meet the requirements of s. 15(1), either as an enumerated or analogous group.

We must also reject the argument that homosexual persons and same *** couples are disqualified from claiming s. 15 discrimination on the basis of either disability or ****** orientation since they are biologically capable of reproduction in a context of heterosexual relationships. Canadian jurisprudence has explicitly recognized ****** orientation as an analogous ground (Egan) and implicit in this classification is a doctrine of constructive immutability, which recognizes that an analogous ground is a characteristic that is immutable or that the State should not be allowed to ask a claimant to change. The inability of a homosexual person to create a biological child within a homosexual relationship without the help of ARTs is therefore implicit under the analogous ground of ****** orientation and once recognized, it remains recognized (as per Andrews, Miron). Since homosexual persons in same-*** relationships are one of only two groups that cannot presumptively conceive without the aid of ATRs, legislative distinctions based on the ability to procreate can be properly seen as discriminating based on ****** orientation. For the purposes of section 15 analysis, the exclusion of homosexual persons from access to the vehicle of commercial surrogacy thus constitutes prima facie ****** orientation discrimination.

When addressing both forms of discrimination present in this case (disability and ****** orientation), we must heed the pronouncement of McLachlin J. (as she then was) in Miron: where a distinction is made on an enumerated or analogous ground it will almost always amount to impermissible discrimination.

C) Discrimination Analysis

This stage of s.15 analysis requires us to answer the following questions: does the law impose a burden or withholds a benefit from the claimant in a manner which violates human dignity. The law either reflects stereotypical application of presumed group characteristics or otherwise perpetuates or promotes the view of inferiority and inequality. Several contextual factors that are endemic to the discrimination analysis are considered below:

i) Pre-existing disadvantage

Same *** couples:

The extensive history of vulnerability and negative stereotyping in regards to homosexual persons is well documented and recognized in Canadian history and jurisprudence. In the absence of ARTs, a legislative distinction between same-*** and opposite-*** couples that is based on simple biological differences in reproductive capability would likely not produce a successful claim for discrimination. The reality, however, is that individual members of a same-*** couple are capable of producing their biological offspring within their family unit through the use of assisted reproduction techniques such as commercial surrogacy. This court has explicitly recognized in M v. H. that an increasing percentage of children are being conceived and raised by couples as a surrogacy and donor arrangements. AHRA provisions prohibiting commercial surrogacy arrangements make it practically impossible for same-*** couples to access these reproductive technologies, creating yet another obstacle for an already disadvantaged group.

Infertile couples

As far as the pre-existing disadvantage of infertile heterosexual couples is concerned, it is an unfortunate truth that the history of disabled persons in Canada is largely one of exclusion and marginalization. The infertile have been shown to suffer pre-existing disadvantage, vulnerability, stereotyping and prejudice. They have been, and seen themselves portrayed as, having undesirable traits or lacking those traits which are regarded as worthy. Furthermore, the stigma that the AHRA imposes on commercial surrogacy is not trivial. The conviction under the Act still carries all the imports for the dignity of the person charged. The petitioners will bear on their record the history of their criminal convictions. This underscores the consequential nature of the punishment and the state-sponsored condemnation attendant to the criminal prohibition.

ii) Ameliorative Purpose or Effects of the Legislation

Section 15 is aimed at preventing discrimination and promoting equality. Therefore, a legislative differentiation may be constitutionally valid if the purpose of the law is to ameliorate or promote a position of another marginalized group. On this point, the Government would likely take the position that sections 6 and 60 of the AHRA are specifically designed to prevent commodification of children and to ameliorate position and status of women in the surrogacy arrangement. Hence, the unintended exclusion of same-*** couples is permissible under s.15 in order to achieve these compelling State goals.

The first interest addressed by the Crown involves the prevention of children from becoming mere commodities in a global marketplace. The prohibition of commercial surrogacy is thus partially anchored in legislative recognition of repugnancy of the selling of parental rights and buying of children. It is indisputable that the State indeed has a legitimate - even paramount - interest in preventing baby selling. The real question is not the validity of such interest but whether commercial surrogacy arrangements are the functional equivalent of baby selling. They are not. In order to characterize the AHRA scheme as a piece of legislation that was necessary to close a legislative gap (surrogacy arrangements as baby selling), the State would need to establish, inter alie, that the law, as it existed before the adoption of the AHRA, treated the babies born to gestational carriers as “goods.”

There is no evidence that law treated the children born through commercial surrogacy as goods. The definition of “good” is not satisfied because not only is the child nonexistent, but the gestational surrogate has no parental rights to the child. On the other hand, the child may still be likened to a “future good.” In order to contract to sell a future good, one must have a right to the future goods at the time of contract. Because a gestational surrogate does hot have legal rights to the child she carries, pursuant to a gestational carriage agreement that she signed, she presumable does not have a right to the future goods at the time of contract. Thus, the child born of a gestational carrier fails to meet the definition of `goods. ” Most importantly, payments made to a surrogate under a contract are meant to compensate her for her services in gestating the fetus and undergoing labor, rather than for giving up “parental” rights to the child.

As the analysis of s.7 interests of surrogates shows, the impugned sections of the AHRA do not achieve their stated purpose of preventing exploitation of women. How, then, does discriminating against same-*** and infertile couples further this goal? Based on the findings contained section 7 analysis, we must conclude that barring homosexual person and infertile couples access to commercial surrogacy cannot be justified on the basis of ameliorative purpose doctrine.

iii) Nature of the Interest Affected

Law test requires us to inquire as to whether a piece of legislation restricts access to fundamental social institution or whether it affects the claimants’ ability to be a full members of a society? In the present case, the interest denied through the operation of the impugned sections of the AHRA is fundamental — namely, same *** and infertile couples’ ability to procreate and build families free from state interference.

Prohibition of commercial surrogacy denies access to the individuals who are incapable of reproducing without the aid of ARTs, to the only practically viable form of procreation despite incontrovertible importance to them of the benefits accorded by the criminalized activity. The disproportionate effect that the prohibition on commercial surrogacy has on same *** couples in particular perpetuates the historical disadvantages suffered by individuals in same-*** relationships. Coupled with this treatment of homosexual persons, a social and psychological suffering that many infertile couples have to endure as a result of criminalization to commercial surrogacy leads to the conclusion that prohibition of commercial surrogacy demeans human dignity of persons in same-*** and opposite *** relationships who are unable to bring a child into this world without the assistance of a gestational carrier.

In light of the purpose of the s.15, the contextual factors and the purposive approach mandated by the Supreme Court, the distinctions drawn by the prohibition on commercial surrogacy are discriminatory and violative of the Charter’s equality guarantee.

D) Violation of Section 15 Rights Is Not Justified under Section 1

To successfully invoke s.1 of the Charter, a party must show that the objective of the impugned law is of sufficient importance to justify limiting the Charter right, and that the means chosen are reasonable and demonstrably justified.

i) The Stated legislative Objective Is Not Pressing and Substantial

It is beyond dispute that the potential exploitation of women and commercialization of children are sufficiently grave concerns that the Parliament is entitled to address. Nevertheless, there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate that exploitation and comodification are real and immediate concerns in the context of commercial surrogacy. The data seem to reflect an absence of significant adverse effects of commercial surrogacy on all participants. AHRA surrogacy prohibitions do not further a pressing and substantial state interest which can justify the intrusion into the private lives of Canadians.

ii) No Rational Connection

The violation of the potential claimants’ rights is not rationally connected to the aim of the AHRA and the policies developed under it. The Act endeavours to prevent exploitation of surrogate mothers and to prohibit the commercialization to babies. Nevertheless, not only does the prohibition against commercial surrogacy not further that goal, but it arguably creates a host of adverse effects on surrogate mothers. Since the prohibition of commercial surrogacy fails to address the mischief that it is purported to remedy, there exists no justification for a denial of benefits to homosexual and infertile persons.

As a policy matter, however, difference must be drawn between the legal treatment of commercial surrogacy in the context of *** or infertile couples and in the context of fertile heterosexual couples. There may indeed exist a sound policy reason in prohibiting fertile couples from entering into a commercial surrogacy arrangement simply as a matter of convenience. In such circumstance, prohibition would serve a valid goal of preventing fertile women from “purchasing a womb” simple because they might feel there is a substitute available, who can undertake her reproductive responsibilities in exchange for money.

iii) Means Chosen Are Not Reasonable and Justified

Prohibition on payments for surrogate mothers’ service beyond reasonable medical expenses unreasonably precludes participation of many willing women in surrogacy arrangements. This prohibition is blind to the reality of lost wages and incidental costs that surrogate mothers would have to incur during pregnancy. The difference in the statutory treatment between commercial and altruistic surrogacy is illusory since the blanket prohibition on compensation ensures that even the most altruistic of women would be unable to afford the surrogacy path.

The prohibition of all forms of commercial surrogacy leaves no venue open to the same *** or infertile couples who are looking to conceive. The unqualified and overbroad denial of access to commercial surrogate services does not leave the claimants with either full panoply or a limited number of options. Rather, the criminal prohibition of surrogacy services eviscerates the potential claimants’ rights entirely.

The criminal prohibition is the most radical legislative solution available to the Parliament to control a private activity. If the intention of the legislature were to prevent exploitation and safeguard the rights of surrogate mothers in commercial arrangements, that goal could reasonably be achieved through the use of more nuanced statutory tools.

The setting-up of a regulatory commission to evaluate and oversee commercial surrogacy arrangements is one of many means more narrowly tailored to achieve this purpose. Despite the problems associated with public accountability of regulatory commissions, criminal law power must be exercised with caution as it is too blunt and rigid a tool to effectively address dynamic and intensely personal area of ARTs. A regulatory commission, with carefully delineated powers would be in a position to ensure proper protection of the legal and personal interests of surrogate mothers. The work of such regulatory body would also guard the interests of the intended parents, meanwhile legitimizing the surrogacy process. When it comes to addressing the changing social attitudes and social science evidence arising in the context of commercial surrogacy, this regulatory approach is far superior to a legislative scheme centered around criminal prohibitions.

In conclusion, prohibition of commercial surrogacy in AHRA is not the least intrusive means of achieving a desired legislative objective of preventing exploitation of surrogate mothers. As such, the discriminatory effects of the AHRA prohibition against commercial surrogacy on homosexual persons and infertile couples cannot be reasonably justified in a free and democratic society. It is imperative to remember that commercial surrogacy contracts are not ordinary commercial contracts. Equating the two would indeed ignore the unique emotional and social dimensions endemic to the surrogacy context. The rules of enforceability and the remedies granted must remain alive to the special nature of the surrogate relationship and be applied with greater flexibility than those claimed under the commercial contract law.

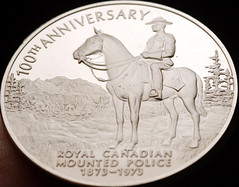

Related Canadian Coin Articles